3. Language in the Insect World

I HAVE told you how, shortly after she discards her wings, the flying queen sends a signal into the air, which is always answered by the appearance of a male flying through the air. What exactly the signal was I did not make clear, but left it for some later opportunity. I want to talk about it now. But I am afraid there will be a long preface before I begin -- perhaps the preface may take even this whole chapter. The inquisitive reader need not be disappointed, however, for I am sure this preface will prove interesting, too. In order to understand the language of animals, one must first of all learn its A B C, but of far more importance are the things you must unlearn. We will therefore begin at the very beginning.

An individual member of any animal race which wishes to communicate with another at a distance can use one of three things; colour, scent or sound. And at this point you must begin unlearning. If you think of colour and scent and sound in terms of the impression which these make on a human being, then you will be lost before you begin your journey. Listen. There is one kind of termite which constantly signals by means of sounds. If ever you have slept in a house in which those termites are at work you will know the sound well. It is a quick tik-tik-tik. You can also hear this if you let down a microphone through a hole made into a termitary. You will easily observe that not only do the termites make this noise, but that other termites at a distance hear it and immediately react to it by their behaviour.

Now catch one or more of the signallers and examine their anatomy under the microscope. What do you find? Not the least sign or suggestion of any kind of auditory organ; not even the most primitive kind of ear; not a single nerve that could possibly be sensitive to what we call sound. We find the same as regards colour and scent. The termites undoubtedly use both colour and scent as a means of signalling -- as you will see later. But again you seek in vain for any organ resembling an eye. There is not even the faintest spot of pigment which might serve as a primitive eye. The termites are quite blind, yet sensitive to an indirect ray of light far below the threshold of perception of the human eye. By this I mean they can become aware of a very diffuse light not shining directly on them, which a human eye could not perceive. This can be proved by experiment. As to any organ of smell, that, too, seems to be completely absent.

Let us now observe another insect, our dear little toktokkie beetle, which will take us a good way along the path we must travel, and will greatly help to explain the secret to us. If you wish to learn to know the toktokkie really well and to learn to talk his language, you must tame him. He must become so used to your presence that he never alters his behaviour by suddenly becoming aware of being observed. He is very easy to tame, at least the gray-bellied one is, and learns to know his master and love him -- you know the one I mean, the smooth little fellow with pale legs, not the rough-backed one. What South African child has never seen the toktokkie and heard him make his knock? Your eye suddenly falls on him in the road or beside it. If he does not get a fright and fall down dead with stiff legs as dead as the deadest toktokkie which ever lived -- then you see him knock, and of course hear him, too. He looks round for some hard object, a piece of earth or a stone, and knocks against it with the last segment of his body -- three, four, four, three! This is his Morse Code. He then listens for a moment or two, turning rapidly in many directions. His behaviour is ridiculously human. His whole body becomes an animated question mark. You can almost hear him saying:

'I'm positive I heard her knock! Where can she be? There, I hear it again!'

He answers with three hard knocks, and then he betakes himself off in great haste and runs a yard or two. He then repeats the signal in order to get a further true direction, and so he continues until at last he arrives at his loved one's side.

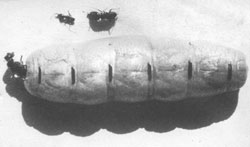

Female termites after shedding their wings

|

If you study the behaviour of many toktokkies during the mating season, you will occasionally have to follow one for an incredible distance in the direction of the answering signal. He can hear the signal over a distance which makes the sound absolutely imperceptible to the human ear. It is at this stage that he begins to rouse the interest of the psychologist. We study him at closer quarters. Again we find under the microscope no sign of an ear, nor complex or nerve which takes the place of an organ of hearing. But in spite of this we still think of the behaviour of the toktokkie in terms of sound and hearing!

Now we will go into our laboratory with our tame toktokkies. The laboratory is a stretch of natural veld or a fairly large garden. The observer will soon discover that the toktokkie is one of the most credulous of insects. When he is dominated by sexual desire, he will believe everything you happen to tell him. Knock on a stone with your fingernail in his own Morse Code -- and at once he answers. You can teach him quite easily never to knock except in answer to your signal. This you succeed in doing by not knocking for several days unless he has become perfectly quiet. After a day or two he will have learnt to knock only in answer to your signal and will answer immediately. Now get a small microphone with headpiece and three feet of wire (you will find this indispensable in your association with the insect world). The microphone must be so powerful that you are able to hear the footfall of a fly quite easily. When your toktokkie is tame and well trained you proceed to test the acuteness of his perceptions. To your amazement you find that they are unbelievably, supernaturally fine. Knock on the stone again with your finger-nail and gradually make the sound softer until it is quite beyond your own hearing. Still the toktokkie answers the signal at once without the least sign of doubt. Then begin knocking not with the nail but with the soft pulp of the finger. There seems to be no sound at all, but still the toktokkie answers! Now take the microphone and place it on the ground with the earphones over your ears. Knock on the receiver with the pulp of your finger -- a real knock, not merely a pressure. With a little practice you can reduce the sound until at last it is inaudible even through the microphone, but still the toktokkie hears it!

The solution to this problem is: It is not sound as such which the toktokkie becomes aware of, and there can be no question of hearing it. Any book of physiology will make it clear to you that sound is only our interpretation of certain vibrations in the atmosphere. (Sound cannot travel through a vacuum -- you can prove this by sending a sound through a wire inserted in the cork of a thermos flask. It will be imperceptible, except for a faint noise which escapes through the cork.) It is our ear which interprets the vibrations as sound. Beyond the ear the universe is soundless. Without an ear -- or organ of hearing -- there can be no sound. But the vibrations which we call sound have a physical function. It is by the exercise of physical force that the drum of the ear and the hammer and anvil bones of the inner ear are set into vibration. In the same way you can let grains of sand or a thin gas-flame vibrate to a musical note. But there is another difficulty. The sudden meeting of the surfaces of two physical bodies can result in vibrations of the mysterious ether, which are not by any means sound-waves and therefore have no effect at all on our ears. We are getting into somewhat deep water now. I believe it is vibrations of this kind, waves in the ether, of which the ants and the toktokkie make use. It may sound far-fetched, but you will have to accept some such explanation if you wish to learn the language of insects. The next time you hear a 'longbreath locust' (apparently so called because it is not a locust and the sound is not made by its breath), you must not think of sound or hearing -- you must think of vibrations -- waves in the ether -- which can be sensed by another such locust at a distance of at least eight miles. You will also have to use this theory when we return to our termite nest, or else you will be forced to think of a miracle in order to explain the communication which takes place between the outlying sections of the nest. This disposes of sound in the insect world. There are two other ways of communication which I must tell you about: Scent and Colour.

A queen termite full of eggs with two soldier termites

|

Our termites continually make use of scents, some of which we can perceive with our olfactory organ. In the Northern Transvaal there is a well-known termite known as the 'stinking ant'; this emits a foul smell to a distance of three or four yards, which has the peculiar property of causing extreme nausea in most people and also in dogs. Then again all South Africans will know the characteristic smell of the common termite. This is caused by the discharge of a gas which the termite uses for other purposes. It is of the utmost importance for us in our study of termite language to make certain of what the signal of the queen really consists. After long study, I have come to the conclusion that it consists of something which would affect our senses as scent if it were strong enough. Things always seem pretty hopeless in the beginning when we are dealing with phenomena which lie far beyond all our senses, but 'perseverance pays' must be the motto of the traveller along these dark and unknown footpaths.

Here is another reason for thinking the signal may be thought of as scent. You can easily train a pointer to track down the flying termites after they have lost their wings. He will track down a signalling queen for nearly a hundred yards against the wind; with the male he finds it difficult even over the distance of a yard.

But a still more important proof will take me longer to explain. The following are all the signals used by the termite:

- The communaI signal which is constantly sent out by the queen -- who forms the hub of the nest. This serves to keep the community together and enables every termite to recognize every other member of the community. It is a signal which cannot be perceived by our senses.

- The call of the workers and soldiers. This is perceived by us as sound.

- Food messages. (Beyond our perception.) These three we will examine more closely later on.

- Lastly, the sexual signal of the queen, which is also beyond the reach of our senses.

We know that throughout nature scent and colour are used as sexuals. If there are no brilliant colours, you may be sure there will be some scent.

Allow me to digress for a moment. I have shown you how the termite flight is the key by which the door to the sexual life is unlocked. Without flight there can be no sexual life. In the mammals the key is generally scent, sometimes allied to colour. This begins in the plant. The colour and perfume of flowers is of course purely a sexual phenomenon. The apes and humans have long ago lost both. But in the other mammals scent still remains as the key which makes sexual life possible -- that is why it is possible to keep large mammals for years in a zoo or menagerie without the sexual passion being awakened. It is interesting to study our African kudus in relation to this fact. In the Waterberg I very often had the opportunity of watching from near at hand a wonderful spectacle. For a week or two every year the kudu cows become scented or 'on heat'. As soon as this passes the bulls leave the cows and segregate themselves to graze in small herds. Of course they come in contact with the cows occasionally but never evince the slightest interest. But just see what happens when the cows, in heat again, travel four or five miles to windward. A minute before all the bulls were grazing peacefully, in sleepy careless fashion. Then they get the wind. It is as if a thunderbolt has fallen in their midst. With fitful movements the beautiful heads are raised and their nostrils are snuffing the wind greedily. Their deafening bellows are heard on all sides, and immediately the whole herd, which a moment before was grazing so peacefully, is lost in a cloud of dust and we hear only the clashing of horns and bellowing of rage, because the sexual life is always preceded by the stimulation of the fighting sense. Without the special scent from the cows, their sexuality would have remained unstimulated. This can be easily proved. Take one of the smaller mammals, of a kind dependent on the sense of smell, and destroy the olfactory nerves by incision; in some cases nature does this with an ulcer. After this the male may be brought into the closest contact with the female, even in heat, but never again will he become sexually stimulated. Outside stimulation, scent or colour, is always essential to stir the sex centres. The only animals whose sex centres can be stirred without this outside stimulation are the higher apes and man. When you come to the ape and man the cultivation of scent and colour becomes fascinating and mysterious. Ask a young woman why she uses the heavenly perfumes which the chemist of our day has learnt the art of producing in such exquisite perfection. Her answer will be misleading, because she does not know the subconscious reason. It is an urge which rises from the most remote recesses of her psyche, a rudimentary and forgotten instinct from the ancient history of her race. She would be startled if she heard the true story of this urge. She would feel embarrassed if she learnt that the basis of all her perfumes were the sexual secretions of several kinds of cats, of deer, and (the most expensive of all) the rudimentary sexual material secreted by a certain kind of whale which is now merely a pathological reminder of his life on the land millions of years ago. Musk is the universal basis of the scent sex signals in animals. Even in human beings this phenomenon may still be found. Our young woman will be astonished and perhaps a little envious, to hear that about one woman in every thousand still secretes musk on occasion. Her whole skin becomes strongly and exquisitely fragrant. As in the case with many such atavistic tendencies of our race history, this secretion of musk is found more frequently in individuals of the monkey or ape tribes. But that is the origin of the mysterious yearning which lovely perfumes awaken in the human being.

When speaking of scent you should again think of waves in the ether. It is false to assume that perfumes consist of gases or microscopic substances. Perfume itself is not entirely a physical substance. You may scent a large room for ten years with a small piece of musk and yet there will not be any loss in weight.

We appear to have gone a very long way round in order to find out of what the signal of our queen really consisted. In reality we avoided many deviations in the path which we might have taken. That shows us how very patient and persevering we must be to reveal the tiniest little secret of our dear Mother Nature. Now at least we are nearly certain -- never of course quite certain -- that the sexual signal of the termite queen is a wave circle in the ether which in all probability would be perceived by our olfactory nerves as perfume if it could cross the threshold of perceptivity of our senses.

Next: 4. What is the Psyche?

Table of Contents

Back to the Small Farms Library